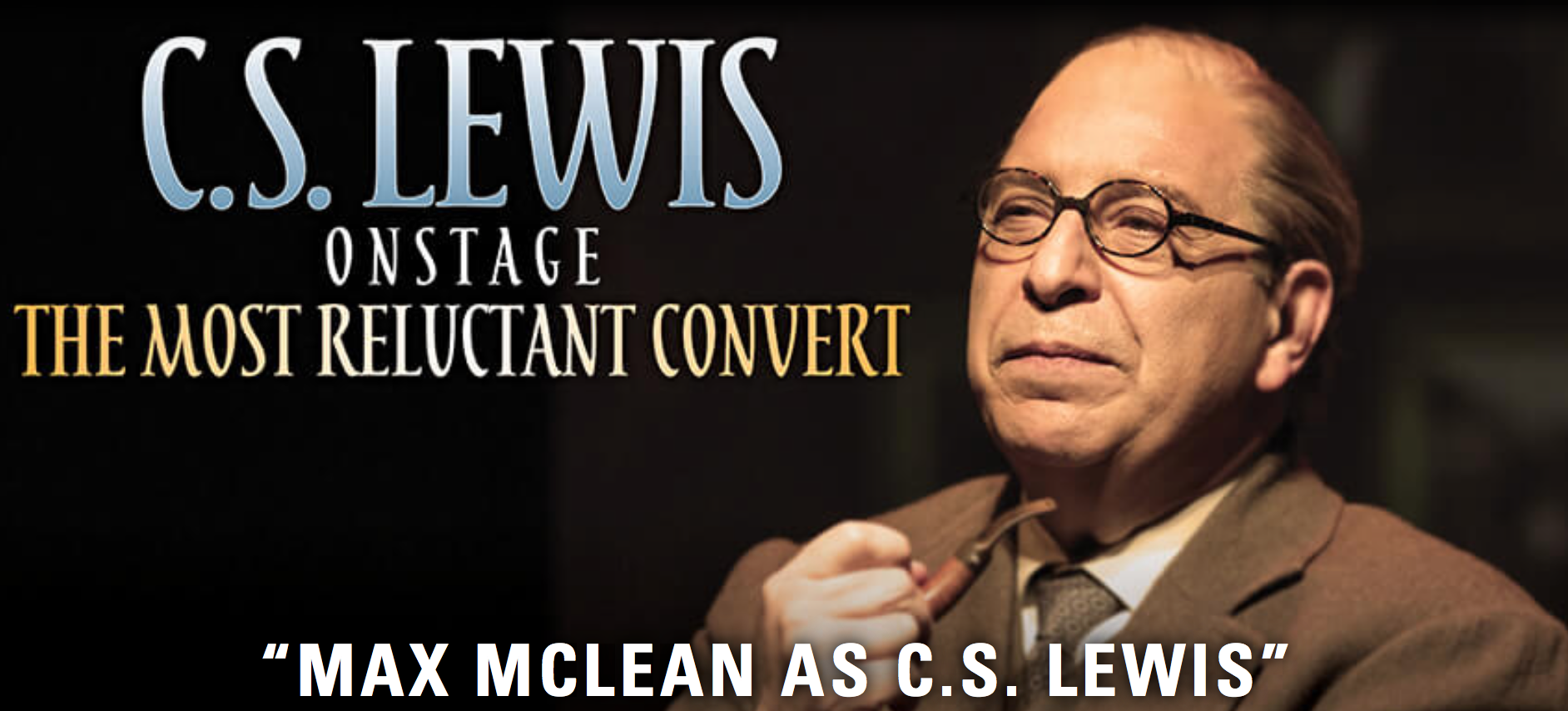

I just saw Max McLean’s one-man stage performance of The Most Reluctant Convert, which dramatically recounts the conversion of C. S. Lewis. It was excellent. If you live near one of the performance locations (currently scheduled in Washington, D.C., San Francisco and Los Angeles), I recommend you take it in.

I also recommend you familiarize yourself with Max’s ministry through The Fellowship for the Performing Arts. Their mission, according to their website, is to “produce theatre from a Christian worldview that engages a diverse audience.” And, based on my experience of enjoying several of their productions, they do so with artistic excellence and class.

I won’t offer a review of The Most Reluctant Convert but will suggest some lessons about evangelism that came through my experience of enjoying the show. McLean crafted a brilliant screenplay based on excerpts and insights from Lewis’ spiritual autobiography Surprised by Joy and many personal letters as well as direct quotes from some other works such as The Problem of Pain, Mere Christianity, and a few of Lewis’ essays. The interweaving of apologetic reasoning, theological digging, and emotional wrestling kept me locked in throughout the 80-minute one-act play.

The content of the show (if I can speak in such a non-artistic way) has similarities to what might be presented at a debate between a Christian and an atheist – with dramatically (pun intended) contrasting results. McLean’s Lewis began his story with an emotional expression of why he was an atheist for the first half of his life. It made perfect sense in light of the cruelty, pain, and suffering that dominates our world.

Thus, the first lesson I want to suggest regarding our evangelism is that we should empathize with our friend’s unbelief rather than attack it from the start. We have a lot of adjusting to do from our usual approach. Many outsiders see a wall between themselves and Christians and our “defenses” often begin by reinforcing and raising the walls even further. If our words, attitudes, and facial expressions convey something like, “I don’t see how you can live without God” or “I don’t have enough faith to be an atheist” or “It’s so obvious!” we push people away unnecessarily.

The opening segment of The Most Reluctant Convert quotes almost verbatim from the first two chapters of Lewis’ The Problem of Pain. Given the realities of evil in our world today, which, it could be argued, are worse than what Lewis grappled with in the early part of the twentieth century, we would do well to affirm our non-believing friends’ temptations to despair.

A second lesson we could learn from this play is the benefit of acknowledging our own internal struggles with conversion. We tend to want to advertise the joys of salvation, forgiveness, and assurance of eternal life. And so we should! But we might also want to weave in admissions of our struggles to surrender, repent, and “lay down our arms.” McLean emoted well about the sadness involved in Lewis’ being pursued by “the steady, unrelenting approach of Him whom I so earnestly desired not to meet.”

Lewis spoke of not only being “the most reluctant convert” but also of being “the most dejected” one. Shouldn’t we include these themes in our testimonies, if indeed they are part of our story? I think some of our skeptical friends would benefit from hearing these kinds of stories more than the “now I am happy all the day” varieties.

Finally, there are advantages of slipping through the side door of the arts and emotions over the frontal assaults of debate and argument. Both are necessary. But I fear we’ve overused the latter while almost ignoring the former. I’ve got some friends I’d like to invite to a play and after-show discussion, who probably won’t go to a debate and after-speech argument. Don’t you?